We engage and invest in research in order to accelerate the pace of scientific discovery, encourage innovation, enrich education, and stimulate the economy — to improve the public good. Communication of the results of research is an essential component of the research process; research can only advance by sharing the results, and the value of an investment in research is only maximized through wide use of its results.

The more people can access and build upon the latest research, the more valuable that research becomes and the more likely people will be able to benefit from it.

Fifteen years ago this month, the Budapest Open Access Initiative first

defined and developed recommendations for open access. The recommendations included the development of policies in institutions, in funding agencies, in licensing, and in the development of repositories.

Submitted by: Steven J. Bell,

Associate University Librarian for Research and Instructional Services, Temple University, US

@blendedlib

What is Open Access?

Here’s what it means to me. It’s a system of free, unfettered access to scholarship, learning content and data in a way that allows it to be widely shared so that all who wish to gain access to it may do so, free of paywalls, access fees, subscriptions or other barriers. Ideally, that content is for more than viewing. The system promotes re-use, re-mixing and re-distribution. An open access scholarly communication system requires a radical departure from what we have now. What open access isn’t are systems that demand authors pay thousands of dollars to publishers in order to set their articles free. What open access isn’t are content systems that claim to be open but bundle in pay-for-access code only resources [see: openwashing]

We can see what an open access system looks like when publishers commit to making their journals freely accessible. Take for example, the research journal College & Research Libraries, published by the Association of College & Research Libraries, a membership organization of 12,000 academic librarians. Several years ago, ACRL committed to “walk the talk” of open access and eliminated journal subscriptions. Now, all of ACRL’s journal publications are completely open, including access to back files. To no one’s surprise, the quality of their journals is strong and in high sought out by potential authors. What makes it possible are members’ dues. Open access does not equal free. But if ACRL can do this, why not other associations that publish journals. A scholarly publishing system that survives primarily because library budgets are funding it is not sustainable.

Let’s remember that open access also means the content is accessible to all.

Why is it important?

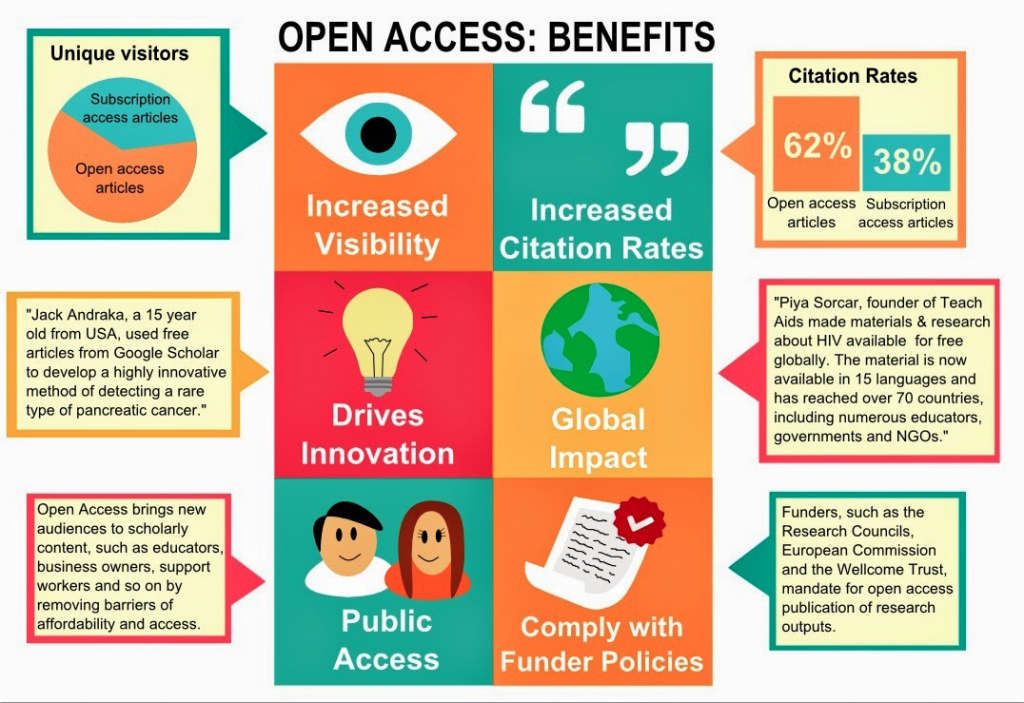

A few years ago there was a great story about a high school student, Jack Andraka, who was able to develop a simple, cost-effective pancreatic cancer diagnostic test. Jack went on to win the 2012 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. His discovery was made possible by Open Access. The open research content in PubMed Central enabled Andraka to get the articles, paywall-free, he needed to develop his diagnostic test.

That’s why open access is important.

That’s one small but important story about how open access can make a difference for the benefit of humanity. Now what if we could multiply that story hundreds or thousands of times. Consider the everyday impact on our college students, faculty and researchers when they have no access? Frustration! Fortunately, academic libraries support each other and their community members through article sharing networks. It helps, but we have to do better. Impediments of any type that add time, hassle or both to the information retrieval process are detrimental to the scholarly communication process. It’s the difference between a life changing discovery and just one more failed idea.

From my perspective as an academic library administrator, and for completely practical reasons, the extreme expense of our closed scholarly communication system is killing us. We don’t have a magic money machine in our library. Our already constrained budgets are regularly imperiled by journal price increases, which suck money away from monographic book buying, technology investment and so many other good things we could do with the funds disappearing into the journal black hole. We can’t afford the current system.

That’s why open access is important. Open access alone won’t make higher education more affordable, but a far more open system of journal publishing would most certainly provide relief to academic library budgets.

What Changes Do You Hope it Will Bring to Your Country?

The health of our nation and its economy depends on our ability to innovate and be more competitive in an increasingly intertwined global economy. When university researchers have access to their journal literature it leads to the discoveries that save time, create efficiencies and improve lives. Why wouldn’t we want to create a scholarly communication system that supports the work of scholarly researchers and business entrepreneurs. Imagine a new startup business operating with limited funds. Perhaps it’s a biomedical firm where a researcher identifies an essential article. Great. Just one problem. It costs $75 to view for 24 hours. That system is hardly conducive to innovation and discovery. That’s a broken system.

Can we blame independent researchers, small business owners and anyone else outside the paywall if they turn to Sci-Hub, a collection of illegally downloaded journal articles? Are we surprised there are highly active underground networks for article sharing. If we can put a sustainable open access journal system into place, sites like Sci-Hub would cease to exist. We’re just not there yet. I hope we will get there and when we do I can envision it doing a world of good for my country, as well as those that are much more content impoverished.

What is the Future of Open Access?

I am far more optimistic that open access will have a healthy future – at least more optimistic than I was ten years ago. We have more open content than ever, whether it’s journal articles, open educational resources, books or other research and learning content. We have better systems for publishing, disseminating and locating our growing universe of open content. The main reason I am more enthusiastic about open access’ future is the change I see taking place among faculty and researchers. Support for open access among faculty is finally spreading beyond the early adopters and revolutionaries. That’s the force we need to secure a sustainable future for open access.

It’s great that the academic library community provides vocal advocacy in support of the open access movement, and sure, we can open up our own literature – though unfortunately too many of my librarian colleagues are still publishing in closed, expensive journals – but to really get to the future of open scholarly communication we must have faculty believing there is a better, more sustainable system than what we have now. As more faculty publish in open journals, adopt open textbooks, teach an open education course, benefit from access to open data, use an open pedagogical learning method and raise their voices about unjust systems that lock down their content, we will evolve institutional cultures of openness.

I am hopeful that the next generation of scholars, perhaps today’s members of Generation Z, will have a much different mindset about and understanding of what it means to openly share content. Will they choose to maintain today’s tenure and promotion systems that drive faculty’s need to publish in the closed, costly journals of their discipline? I think we will see different reward systems emerging. We can shift from a broken scholarly publishing system to one that systemically fosters the culture of openness across all the generations. Events like Year of Open generate awareness and help to weave the openness culture that slowly but surely will bloom around the world.

Submitted by: Helen Blanchett

Scholarly communications subject specialist

Jisc, UK

@hblanchett

Open Education Consortium, Helen Blanchett, Scholarly communications subject specialist at Jisc

I am currently the scholarly communication subject specialist at Jisc, where I have responsibility for ensuring the quality of our support and engagement activities. My background is originally as a librarian, but I have spent most of my career delivering training and staff development in the education sector.

What is Open Access?

Open access refers to making the outputs of research available to anyone to access. The term can be used to cover different levels of openness, from simple ‘read’ access through to being able to remix and reuse content. The Budapest Open Access Declaration is commonly cited as a definition, which includes reuse rights. The intention of open access is to encourage free exchange of knowledge and resources in order to widen access and encourage creativity. Jisc has produced a short guide to explain open access.

Why is it important?

Open access to research has a wide range of benefits for all aspects of society, from enabling faster and better quality research, supporting innovation in the economy to enabling access to those who cannot afford to pay for journal subscriptions. It is also about fairness – much research is funded by the taxpayer and so should be widely available and not require payment to access. In the UK most research funders now mandate that journal articles are made available open access.

What changes do you hope it will bring (for your country/region)?

One of the great things about open access is that it has the potential to benefit everyone around the world. The benefits to society and economy should be felt in the UK as well as more widely. OA can however raise the profile and reputation of the UK’s research activity and universities, as OA outputs have been found to receive more citations.

What is the future of Open Access?

Hopefully open access is here to stay, as the benefits it brings are so wide-ranging. There are still challenges around supporting institutions and individual researchers with the move to open access – it’s an area Jisc has supported in the UK through our Open access good practice project. We have produced a handbook to support institutions in the challenges they face in implementing OA, including sections on advocacy, policy compliance, cost management, structures and workflows, and metadata and systems interoperability.

The types of research output being made available openly is broadening. As well as open access to journal articles, there is an increasing move towards open access monographs and in the UK we are seeing the launch/relaunch of several University Presses to support this. Making the underpinning research data open is already mandated by several research funders, which leads to opportunities to replicate or build on previous findings, hopefully improving research quality.

In the UK we are increasingly starting to talk about open research / scholarship more generally. So less focus simply on research outputs, but making the whole process of research more open, including sharing early ideas and finding collaborators, developing proposals, publishing pre-prints and open peer review. At Jisc we are exploring how we can best support these developments through our open access services and our research and development activity.

Submitted by: Dr Siân Harris

Publications and Engagement Manager

INASP, UK

@INASPinfo

What is Open Access?

At its simplest, open access is about the published results of research being openly available to anybody who wants to read and use them. But open access in practice isn’t that simple. Over the past couple of decades there have been many long and often heated discussions about how to do this in practice. Some have favoured the institutional and subject repository approach where open access is essentially an overlay on the traditional subscription model. Others have favoured a shift in business models where there is a payment to publish research rather than a payment to read that research.

In recent years, the latter has emerged as more dominant, with strong support in the form of government mandates and publishers that want to want to cover their costs and ensure an ongoing revenue stream. There are advantages of this so-called ‘gold’ approach in discoverability and consistency, for example. Greater clarity about licences and permissions can enable more far-reaching reuse of articles and their underlying data.

However, there are challenges. The two that we particularly see in our work with researchers in developing countries are the potential costs of paying to publish and the challenge of avoiding rogue publishers and journals.

Why is it important?

For INASP, an international-development organization with a vision of research and knowledge at the heart of development, the underlying principle of open access is very important. Researchers in low- and middle-income countries – just like researchers in high-income countries – need access to high-quality research in order to do good research themselves. Open access is also very important for developing-country researchers to communicate their research to peers, practitioners and policymakers in their country, who may otherwise have problems knowing about and accessing local research output, as well as to researchers in other parts of the world.

We don’t take a particular stance on how this is achieved and over the course of our 25-year history we have been involved in many different approaches.

INASP began as an intermediary, negotiating free and low-cost access to research information for researchers in the developing world. That work continues and today we work with over 50 international publishers making over 55,000 electronic journals and 30,000 electronic books (2016 figures) available to over four million researchers and students in 1,600 institutions in Africa, Asia and Latin America. You can see some of why this is important in this short video.

We also support Southern publishing, especially journals that are free to read, and have set up and manage Journals Online platforms across the regions we work in.

Over the course of our history, we have also supported institutions to establish repositories and we, in conjunction with UNESCO, provide annual small grants to Southern institutions and projects looking to promote open access.

We recently published a case study about how one of these grants was used to train rural health workers in Tanzania on how to use open access materials. One doctor said, as a result of this training:

“I didn’t know that I could access online resources for free … I now hope I can use my smartphone to do wonders in my clinical practice.”

We have also just published a video interview that shares the thoughts on open access of one of the researchers in our AuthorAID network, Joshua Okonya, a crop entomologist in Uganda. He said in a case study: “With my Open-Access publications, I am advancing science [and] agricultural development but above all providing baseline information to students, researchers and development partners with the hope of improving food security and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Uganda.” Click here to watch the video or here to read Joshua’s case study.

What changes do you hope it will bring (for your country/region)?

We hope – and aim – for good access to information for Southern researchers to enable good research and, through this research, directly or indirectly, for lives to be improved.

Much has already happened to improve access but we recognise that many barriers to research equality remain. In terms of open access, I’d like to return to the two challenges I particularly mentioned earlier: costs of paying to publish and rogue publishing practices.

Through the annual Publishers for Development conference, INASP has been working with publishers to encourage responsible business practices as countries develop and move from being recipients of philanthropy to being customers of publishing companies. Our INASP Principles for Responsible Engagement advise on issues such as clear communication of pricing and any pricing changes, and understanding country context. These principles are equally applicable to publishers charging article processing charges (APCs), and considering offering APC waivers, for open access publication. This will be a strong theme of this year’s Publishers for Development conference.

We also see a real challenge with journals with bad publishing practices – often called predatory journals. These are damaging for researchers who are tricked into publishing in them and also potentially for legitimate Southern journals that risk getting tarred with the same brush. INASP is a founder member of the Think. Check. Submit. campaign which aims to educate researchers on choosing appropriate journals for their research. We also provide guidance to researchers through our AuthorAID network.

What is the future of Open Access?

Open access is clearly here to stay and it is encouraging to see the principles of openness making a difference to research communication worldwide. It is still a complex picture and we see that many researchers are still unclear about aspects of it.

At INASP, our focus is not on open access itself but on what that access enables. We hope that open access will play a role in a future where research and knowledge from all over the world will be able to help people wherever they are in the world.