So you’ve digitized museum and archive collections. You’ve given them open licences so copyright isn’t a barrier to use. You’ve provided high quality files for download. Now what?

One of the main reasons so many people are working so hard to create open culture is to give everyone, whoever and wherever they are, the opportunity to use amazing and fascinating cultural material in their own personal and professional projects.

New ways of looking at the world

A branch of Europeana’s work, called Europeana Research, is dedicated to encouraging the use of cultural material in academic research. Last year, as part of the Europeana Research Grants Programme, it awarded three researchers funding for projects that used cultural heritage collection material from Europeana Collections.

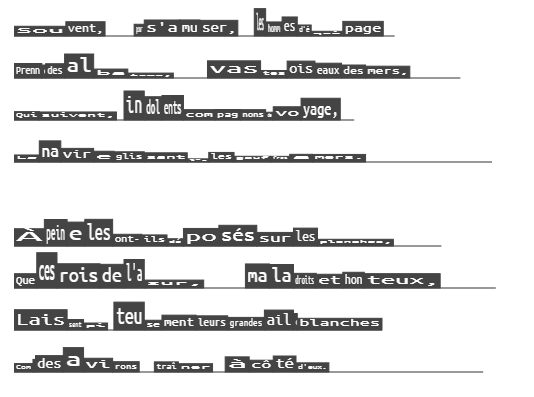

Example from the Visualising Voice project, using L’Albatros by Charles Baudelaire.

Caroline Ardrey is a post-doctoral researcher who won the grant to help her analyse spoken performances of 19th-century French poetry through her project Visualising Voice. Caroline says, ‘My project is all about highlighting the fact that cultural heritage resources and digital humanities tools aren’t about us and them, that exploring the findings of research doesn’t always need to be mediated by the voice of the academic – anyone can try their hand at engaging directly with the resources in Europeana Collections, because they’re publicly available. It was essential to me to make Visualising Voice a “democratic” project, which didn’t just show a non-academic audience what people are doing in universities, libraries and cultural heritage institutions, but rather that it gave them a chance to have a go at carrying out digital archival research for themselves.’

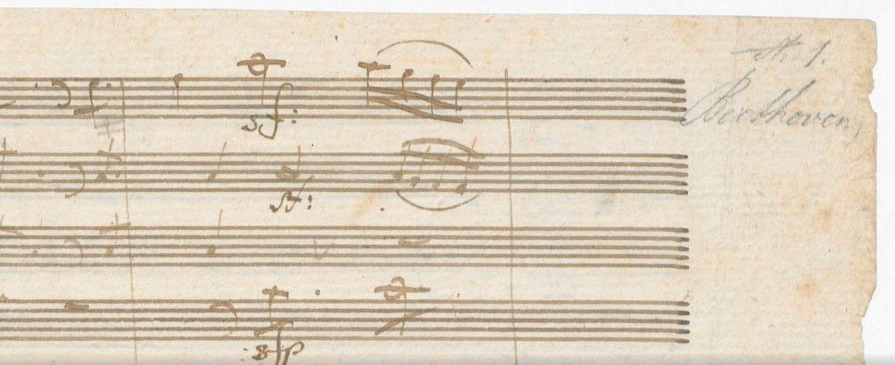

Ah ! perfido, op. 65 : fragment (manuscrit autographe) / Ludwig van Beethoven, National Library of France, 1796, public domain.

Dr Timothy Duguid won the grant for work on his research portal MuSO (Music Scholarship Online). ‘MuSO will aggregate digital archives and collections, digitized printed scholarship, and born-digital scholarly resources in music alongside other humanities-related digital artefacts,’ says Tim. ‘Access to cultural heritage data is critical for MuSO. In fact, the community surrounding this project is all dedicated to promoting greater visibility and access to music heritage artefacts and data. It is our goal that MuSO will allow scholars to discover high quality digital scholarship alongside primary musical resources and more traditionally disseminated forms of scholarship such as digitized monographs and electronic journal articles.’

View of “Kastellet”, Copenhagen | Johan Rohde, Nationalmuseum, Sweden, public domain

Nanna Thylstrup and Lene Asp work together on a project called ‘Mapping a Colony’, a digital map of Copenhagen tracing the historical and contemporary presence of Danish colonies in the urban landscape. Lene says, ‘Cultural heritage data is essential for the presentation of material on the digital platform we are creating, of course we also rely on written sources, but the project itself would not be possible without access to digital material.’ And Nanna expands, ‘Europeana’s transnational platform makes it possible to work across national archives. This is particularly valuable when working with European colonial history that was – and remains – entangled across borders. But Europeana also provides a great opportunity to examine, not only in theory, but also in practice how digitization not only opens up to new ways of working with colonial archives, and thus new modes of knowledge production, but also how they give rise to new ethical, political and methodological questions.’

Want to know more?

Find out more about open culture and research with Europeana.