‘The kinds of new creative works, commentary, and research open culture enables benefit our ongoing dialogue about who we are, where we came from, and where we are going.’

Today, we’re talking to Franky Abbott, Curation and Education Strategist for the Digital Public Library of America.

The Digital Public Library of America brings together the riches of America’s libraries, archives, and museums, and makes them freely available to the world. Follow the DPLA on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr.

Why is open culture important to you? Why do you get out of bed each day to do this?

Open culture enables widespread access to resources that previously required time, money, or geographic proximity to consume. Not only can anyone with an Internet connection access these resources for various kinds of research, they can use these resources to create and inspire new work. For me, open culture is a critical step towards lowering barriers to engagement with our shared culture and history and facilitating new kinds of commentary and expression. As a former academic and secondary teacher, I’ve witnessed the ways in which the cost of subscriptions and travel to archives sharply limits use and shapes engagement with archival materials as a more elite practice. There will always be an audience for analogue archival materials—digital sources are not a substitute for that, just a different way to experience a piece of content. Many archives are doing work to get new patrons in their doors and lower barriers for access, but I love the ways open culture is also helping to overcome these entrenched problems.

Who benefits from open culture and how?

Open culture has many beneficiaries: creators and researchers who use open culture resources, the cultural institutions that make them available, societies more generally. For users of open culture resources, the availability and open licensing of the materials allows them to discover new sources and employ them in various ways to produce new artwork, social and political commentary, historical arguments, whimsical gifs, etc. Open culture greatly expands this pool of available material and lowers traditional barriers to access, which in turn allows a much larger group of users to engage with it. For cultural institutions that put up the staff time and money to digitize materials and relinquish some traditional control over who uses them and how, there is also major benefit in increased use of the materials. This use is a core tenant of the mission of most cultural institutions, which are designed to share art, history, culture with patrons for educational and other purposes. Finally, in the broadest terms, we all benefit from open culture! The kinds of new creative works, commentary, and research it enables benefit our ongoing dialogue about who we are, where we came from, and where we are going.

Can you tell us about a successful project / achievement using open culture resources?

As the Curation and Education Strategist at the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), my job is to use open culture resources to tell stories. We do that many ways—through online exhibitions and, more recently, by designing Primary Source Sets for educators and students. Working with a team of terrific educators from secondary and college teaching, we select primary sources from DPLA’s contributing institutions that give students important insight into people, places, events, and ideas that are part of their curriculum, like the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Social Realism. Primary sources are an incredibly important set of materials for students because they are the raw materials of history that help develop context for a particular historical or cultural moment. By asking teachers with expertise in teaching with primary sources to curate open culture resources for this purpose, we are helping a much larger pool of educators and students connect with materials they can use while eliminating time-consuming searching and sorting.

Why is it important for these resources to be available freely?

In the case of DPLA’s Primary Source Sets, it is important for these materials to be freely available because of their high instructional value as well as teachers’ natural practices of adapting and remixing content to serve the needs of a particular course, unit, or student. It is essential that educators have the flexibility to do this with educational material and open culture allows that to happen. Because so much educational content is available via subscriptions or other products that require purchasing, student access to high-quality materials has historically been mitigated by the budget of the schools they attend, the decisions of high-level administrators, the availability of money to purchase products for individual courses. Use of projects like the Primary Source Sets does still require access to the Internet, which is a real barrier for some, but it is a step towards improving access for a broad range of students and teachers.

What is the future of open culture? If you were Elon Musk, what would you do with open culture?

Hm. I’m not sure I have an Elon Musk-level answer to this question. But I’ll say that one important concern for me with open culture is thinking more specifically about organization to facilitate use. Many open culture projects house a vast multitude of resources accessible to users, which is wonderful. (I work for a national digital library that currently provides access to more than 16 million items, for example.) But discovering open culture resources often requires a lot of users because the experience is heavily search-based. Platforms that host open culture resources often favour users with very specific research questions and search experience who are willing and/or expert enough to drill down through a huge quantity of content. I’d love to see the stewards of open culture focus in on organization, metadata for a global audience, subject groupings, storytelling, as ways to remove some of these challenges for users who will be less successful with laborious search and refine methods.

What cultural resources do you like to access online, personally?

Well, I am an American history nerd so I’m always interested in open culture collections that facilitate my own research, for example, open content from the United States National Archives or the New York Public Library. I’m also interested in the ways that open culture resources can give us access to untold stories and underrepresented communities. The Real Face of White Australia/Invisible Australians was one of the projects that got me deeply invested in this work. Like millions of other people, I am also a lifelong learner (or armchair researcher) who relies on materials made available by projects like Wikipedia to do quick research on a timely topic of interest. And I love art, so I am always giddy about the release of artworks from museums, like the recent announcement from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What is your favourite piece of digitized culture, e.g. favourite artwork?

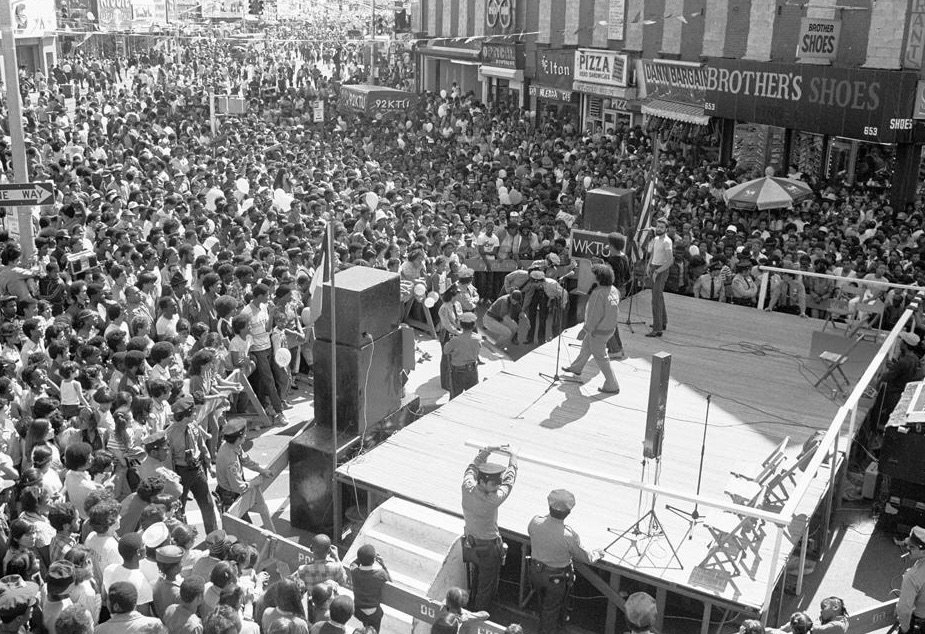

I can only choose one? That’s so tough. Cornell University has made available a collection of more than 7,000 photographs by the American hip hop photographer Joe Conzo that are spectacular. I love those photographs and I’m so grateful that they are available for lots of people to learn from and enjoy.

Joe Conzo, “The Mean Machine performing at street festival, Third Ave. Hub, Bronx, 1981.” Courtesy of Cornell University via ArtStor.

Available via DPLA: https://dp.la/item/be02f1dd085505b36a8d0d910900822d and ArtStor: http://search.openlibrary.artstor.org/object/SS7729596_7729596_3045838_CORNELL.